Practicing: On Meditation Practice

by Karla Beatty

There are various ways to begin a meditation practice. Here spiritual leaders

and meditation masters share their instructions for getting started.

and meditation masters share their instructions for getting started.

|

|

Beginning Meditation Practice --by Karla Beatty

Posture, breathing, and attitude are the entryways into meditation and mindfulness. Learning how to meditate often involves finding your own way by listening to others. Here are some insights and instructions from spiritual leaders Thich Nhat Hanh, Sunryu Suzuki, Jules Shuzen Harris, and Sharon Salzberg.

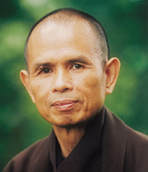

Thich Nhat Hanh

Some people sit in the lotus position, the left foot placed on the right thigh and the right foot placed on the left thigh. Others can sit in the half lotus, the left foot placed on the right thigh, or the right foot placed on the left thigh. There are people who are not comfortable in either of those positions who sit in the Japanese manner, the knees bent, resting on their two legs. Even so, anyone can learn to sit in the half lotus, though at the beginning it may be somewhat painful. After a few weeks of practice, the position gradually becomes quite comfortable. During the initial period, when the pain can be bothersome, alternate the position of the legs or change to another sitting position. If one sits in the lotus or half-lotus position, it is necessary to use a cushion to sit on so that both knees touch the floor. The three points of bodily contact with the floor created by this position provide an extremely stable position.

Some people look on meditation as a toil and want the time to pass quickly in order to rest afterwards. Such persons do not know how to sit yet. If you sit correctly, it is possible to find total relaxation and peace right in the position of sitting.

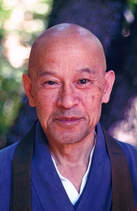

Shunryu Suzuki

Now I would like to talk about our zazen posture. When you sit in the full lotus position, your left foot is on your right thigh, and your right foot is on your left thigh. When we cross our legs like this, even though we have a right leg and a left leg, they have become one. The position expresses oneness of duality: not two, and not one. This is the most important teaching: not two, and not one. Our body and mind are not two and not one. If you think your body and mind are two, that is wrong; if you think that they are one, that is also wrong. Our body and mind are both two and one. And even though we say mind and body, they are actually two sides of one coin. This is the right understanding. So when we take this posture it symbolizes this truth. When I have the left foot on the right side of my body, and the right foot on the let side of my body, I do not know which is which. So either may be the left or the right side. The most important thing in taking the zazen posture is to keep your spine straight. Your ears and your shoulders should be on one line. Relax your shoulders, and push up towards the ceiling with the back of your head. And you should pull your chin in. When your chin is tilted up, you have no strength in your posture; you are probably dreaming. Also to gain strength in your posture, press your diaphragm down towards your hara, or lower abdomen. This will help you maintain your physical and mental balance. When you try to keep this posture, at first you may find some difficulty breathing naturally, but when you get accustomed to it you will be able to breathe naturally and deeply. Your hands should form the “cosmic mudra”. If you put your left hand on top of your right, middle joints of your middle fingers together, and touch your thumbs lightly together (as if you held a piece of paper between them), your hands will make a beautiful oval. You should keep this universal mudra with great care, as if you were holding something very precious in your hand. Your hands should be held against your body, with your thumbs at about the height of your navel. Hold your arms freely and easily, and slightly away from your body, as if you held an egg under each arm without breaking it. You should not be tilted sideways, backwards, or forwards. You should be sitting straight up as if you were supporting the sky with your head. This is not just form or breathing. It expresses the key point of Buddhism. It is a perfect expression of your Buddha nature. If you want true understanding of Buddhism, you should practice this way. These forms are not a means of obtaining the right state of mind. To take this posture itself is the purpose of our practice. When you have this posture, you have the right state of mind, so there is no need to try to attain some special state. When you try to attain something, your mind starts to wander about somewhere else. When you do not try to attain anything, you have your own body and mind right here. A Zen master would say, “Kill the Buddha!” Kill the Buddha if the Buddha exists somewhere else. Kill the Buddha, because you should resume your own Buddha nature.

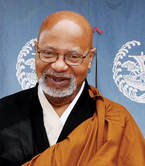

Jules Shuzen Harris

There has been a lot of attention recently on the many practical benefits of meditation. It reduces stress, lowers blood pressure, and is effective in working with depression, anxiety, and anger. These are all good reasons to meditate, but ultimately Buddhists practice zazen and other meditations to realize what Buddhism calls our true nature, which is beyond self-identity with its self-imposed limitations. From a Buddhist perspective, our main problem is attachment to our deluded idea of who we are, and what we need to do to maintain this delusion. You should preferably sit in the morning, starting with ten minutes a day for the first week. As your practice develops, gradually work up to 20-30 minutes a day. Here are some simple instructions to get you started: Space Find a quiet space to sit. It may help to create an uncluttered space, free of as many distractions as possible. Working to create an outwardly clear, calm space reflects our care for our practice and also supports the interior aspects of our zazen. A zabuton (soft mat) and zafu (cushion) will offer support for upright sitting. Posture Give careful attention to your body and posture. If you are just starting out, try a number of different ways to sit in order to find one that’s comfortable for you. There are several options. Sit with both legs crossed so each leg rests on the opposite thigh (full lotus); sit with one leg resting over the opposite calf (half lotus); sit on your knees with your legs folded under you, straddling a cushion like a saddle; sit on a low bench with your legs tucked under the bench; or sit in a straight-back chair. Comfort The sitting position that works best for you will depend in part on your flexibility. Stretching prior to each sitting will help alleviate tightness and discomfort. As your meditation practice evolves, the pain you may experience at the outset will become less of an issue. Though there may be some discomfort as the limbs stretch in unfamiliar ways, gradually the body adjusts. Attention Whatever position you choose, your back and head should be erect. Your ears should line up with your shoulders and your chin should be slightly tucked in. Sit quietly with your eyes open and unfocused. Lower your gaze to a 45-degree angle. Bring your attention to your breathing. First, inhale and exhale through your mouth while rocking right to left three times. Bring your hands together forming a zazen mudra (left hand resting on right hand with the palms facing up and the tips of the thumbs just touching). Breath Now you are ready to concentrate on your breath. Focus on the inhale and count one, then focus on the exhale and count two. Inhale again, counting three, and exhale again, counting four. The goal is to get to a count of ten without thoughts crossing your mind. If thoughts come up, start over at one. Breathe through your nose in a natural, unforced rhythm. Thought Refrain from trying to stop your thinking—let it stop by itself. When a thought comes into your mind, let it come in and let it go out. Your mind will begin to calm down. Nothing comes from outside of mind. The mind includes everything; this is the true understanding of the mind. Your mind follows your breathing. While you are following the breath, drop the notion of “I am breathing.” No mind, no body—simply be aware of the moment of breathing. Drop the ideas of time and space, body and mind, and just “be” sitting.

Sharon Salzberg

This classic meditation practice is designed to deepen concentration by teaching us to focus on the in-breath and out-breath. Sit comfortably on a cushion or a chair. Keep your back erect, but without straining or overarching. (If you can’t sit, lie on your back, on a yoga mat or folded blanket, with your arms at your sides.) Close your eyes, if you’re comfortable with that. If not, gaze gently a few feet in front of you. Aim for a state of alert relaxation. Deliberately take three or four deep breaths, feeling the air as it enters your nostrils, fills your chest and abdomen, and flows out again. Then let your breathing settle into its natural rhythm, without forcing or controlling it. Just feel the breath as it happens, without trying to change it or improve it. You’re breathing anyway. All you have to do is feel it. Notice where you feel your breath most vividly. Perhaps it’s predominant at the nostrils, perhaps at the chest or abdomen. Then rest your attention lightly—as lightly as a butterfly rests on a flower—on just that area.Become aware of sensations there. If you’re focusing on the breath at the nostrils, for example, you may experience tingling, vibration, or warmth, itchiness. You may observe that the breath is cooler when it comes in through the nostrils and warmer when it goes out. If you’re focusing on the breath at the abdomen, you may feel movement, pressure, stretching, release. You don’t need to name these sensations—simply feel them. Let your attention rest on the feeling of the natural breath, one breath at a time. (Notice how often the word “rest” comes up in this instruction? This is a very restful practice.) You don’t need to change it, force it, or “do it right”: just feel it. You don’t need to make the breath deeper or longer or different from the way it is. Simply be aware of it, one breath at a time. You may find that the rhythm of your breathing changes. Just allow it to be however it is. Sometimes people get a little self-conscious, almost panicky, about watching themselves breathe—they start hyperventilating a little, or holding their breath without fully realizing what they’re doing. If that happens, just breathe more gently. To help support your awareness of the breath, you might want to experiment with silently saying to yourself “in” with each inhalation and “out” with each exhalation, or perhaps “rising” and “falling.” But make this mental note very quietly within, so that you don’t disrupt your concentration on the sensations of the breath. Many distractions will arise—thoughts, images, emotions, aches, pains, plans. Just be with your breath and let them go. You don’t need to chase after them, you don’t need to hang onto them, you don’t need to analyze them. You’re just breathing. Connecting to your breath when thoughts or images arise is like spotting a friend in a crowd: You don’t have to shove everyone else aside or order them to go away; you just direct your attention, your enthusiasm, your interest toward your friend. “Oh,” you think, “there’s my friend in that crowd. Oh, there’s my breath, among those thoughts and feelings and sensations.” If distractions arise that are strong enough to take your attention away from the feeling of the breath—physical sensations, emotions, memories, plans, an incredible fantasy, a pressing list of chores, whatever it might be—or if you find that you’ve dozed off, don’t be concerned. See if you can let go of any distractions and return your attention to the feeling of the breath. Once you’ve noticed whatever has captured your attention, you don’t have to do anything about it. Just be aware of it without adding anything to it—without tacking on judgment (“I fell asleep! What an idiot!”); without interpretation (“I’m terrible at meditation!”); without comparisons (“Probably everyone can stay with the breath longer than I can!” or “I should be thinking better thoughts!”); without projections into the future (“What if this thought irritates me so much I can’t get back to concentrating on my breath? I’m going to be annoyed for the rest of my life! I’m never going to learn how to meditate!”). You don’t have to get mad at yourself for having a thought. You don’t have to evaluate its content, just acknowledge it. You’re not elaborating on the thought or feeling. You’re not judging it. You’re neither struggling against it nor falling into its embrace and getting swept away by it. When you notice your mind is not on your breath, notice what is on your mind. And then, no matter what it is, let go of it. Come back to focusing on your nostrils or your abdomen or wherever you feel your breath. The moment you realize you’ve been distracted is the magic moment. It’s a chance to be really different, to try a new response. Rather than tell yourself you’re weak or undisciplined, or give up in frustration, simply let go and begin again. In fact, instead of chastising yourself, you might thank yourself for recognizing that you’ve been distracted, and for returning to your breath. This act of beginning again is the essential art of the meditation practice. Every time you find yourself speculating about the future, replaying the past, or getting wrapped up in self-criticism, shepherd your attention back to the actual sensations of the breath. If it helps restore concentration, mentally say “in” and “out” with each breath, as suggested earlier.) Our practice is to let go gently and return to focusing on the breath. Note the word “gently.” We gently acknowledge and release distractions, and gently forgive ourselves for having wandered. With great kindness to ourselves, we once more return our attention to the breath. If you have to let go of distractions and begin again thousands of times, fine. That’s not a roadblock to the practice—that is the practice. That’s life: starting over, one breath at a time.If you feel sleepy, sit up straighter, open your eyes if they’re closed, take a few deep breaths, and then return to breathing naturally. You don’t need to control the breath or make it different from the way it is. Simply be with it. Feel the beginning of the in-breath and the end of it; the beginning of the out-breath and the end of it. Feel the little pause at the beginning and end of each breath.Continue following your breath—and starting over when you’re distracted—until you’ve come to the end of the time period you’ve set aside for meditation. When you’re ready, open your eyes or lift your gaze. Try to bring some of the qualities of concentration you just experienced—presence, calm observation, willingness to start over, and gentleness—to the next activity that you perform at home, at work, among friends, or among strangers. |

|

Meditation (or mindfulness practice) is a beautiful way to stay grounded. It teaches us to be in the present moment so that we can savor the good times while better managing the trying ones. It helps us to stay connected with our true essence, building our sense of self-love and worth. Studies have linked mundfulness to better concentration, increased focus, and boosts of memory. There are numerous ways to work with the mind. One of the most effective is through the tool of meditation.

Read more articles like this about meditation and mindfulness.

|

|

Author: Karla Beatty About

|